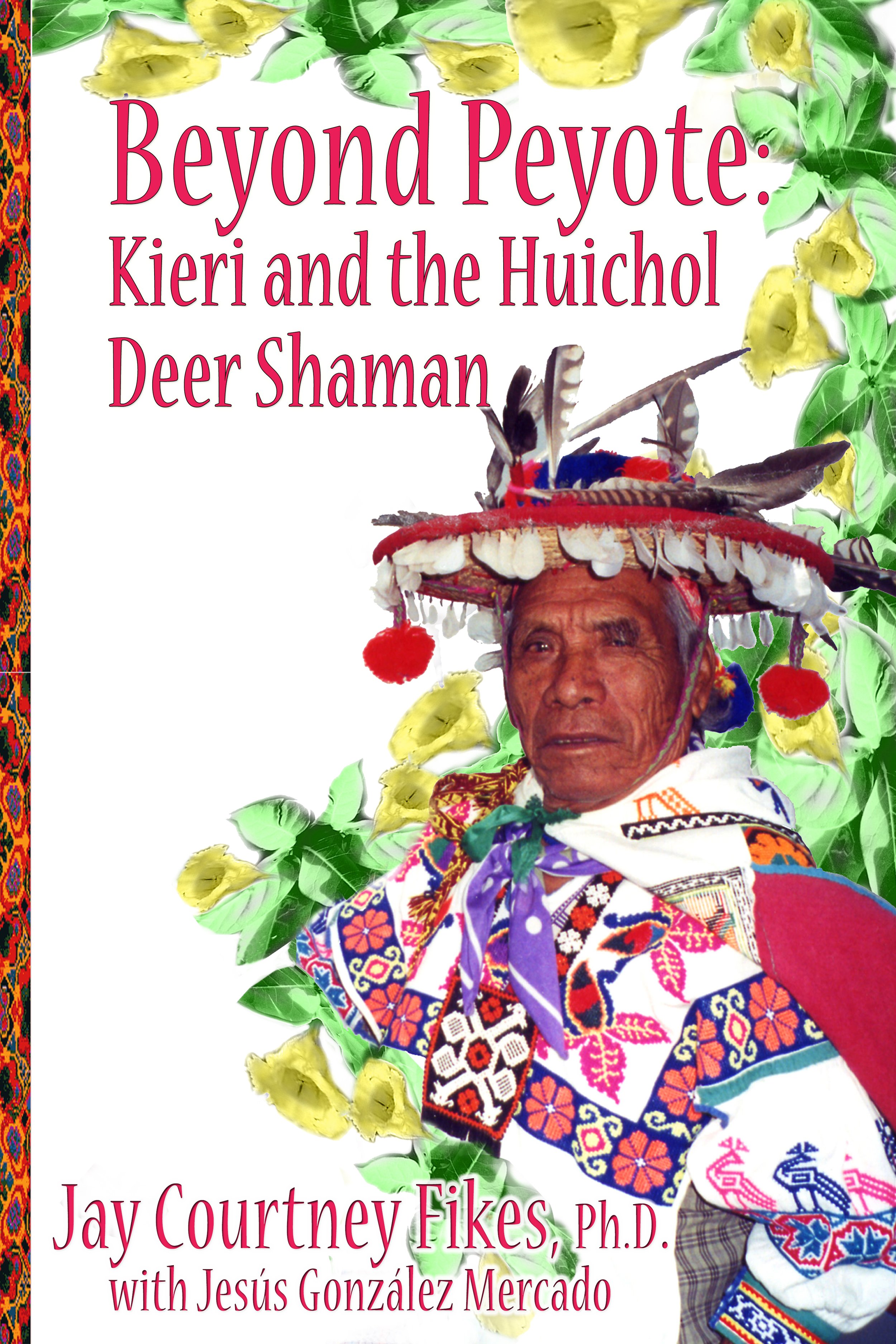

BEYOND PEYOTE Kieri and the Huichol Deer Shaman

by Jay Courtney Fikes, Ph.D.

with Jesús González Mercado

paperback / $40 / 978-1-58790-581-0 / 278 pages / 6" x 9" / illustrated / color

hardback / $60 / 978-1-58790-582-7 / 278 pages / 6" x 9" / illustrated / color

e-book / 978-1-953807-02-1

SUBJECTS: Entheogens, psychedelics, shamanism, Huichol, peyote, Carlos Castaneda, Phil True, marijuana, shamans, anthropology of religion, mythology, ritual, Wixarika

ABOUT THE BOOK

Beyond Peyote: Kieri and the Huichol Deer Shaman is anchored by the biography of a Huichol shaman who did not depend upon peyote, a manifestation of their world-famous tutelary spirit. Instead, at age seven Jesús González unwittingly ingested psychoactive honey made from nectar of a more potent divine plant, Kieri, in the genus Solandra. Eating such singular honey allowed González to discern that the spirit of Kieri—revered by Huichol as their “Elder Brother”—was selecting him to serve as a shaman. His detailed description of seeing and hearing Elder Brother’s invitation to become a shaman provides a glimpse into the world experienced by Huichol shamans. Some 45 years later, Jesús González and one of his two wives became sick, a sign they were being punished for disregarding the gift Elder Brother had bestowed upon him. To atone for failing to heed the shamanic call of his childhood Jesús and his wife began performing rituals to honor Ancestor-Deities controlling natural phenomena vital to Huichol survival. Doing so enabled Jesús and his wife to regain their health. Jesús soon began healing his relatives.

González offers abundant information explaining how he treated and diagnosed diseases. He also clarifies how his father and grandfather became shamans. To provide a complete account of Huichol shamanism González chose Jay Fikes to interpret and publish his all-inclusive narrative of the divine birth and life of the first Huichol Deer Shaman. His entertaining narrative of Elder Brother’s birth, from a pollinated Kieri flower, transformed into a boy because of a childless couple’s prayers and offerings, illustrates why Huichol shamans should practice compassion, integrity and truthfulness, virtues indispensable to effectively serve their people. Beyond Peyote cites ample evidence supporting the conclusion that although Huichol venerate both peyote and Kieri as incarnations of Elder Brother, Kieri is perceived as the more powerful and ancient entheogen.

Fikes also discusses chronic problems stemming from extreme poverty prevalent among those traditional Huichol still inhabiting their rugged mountain and canyon homeland surrounding the Chapalagana River Valley in northwest Mexico. Exemplary in this regard is the involvement of some Huichol in small scale marijuana cultivation, dating to the mid 1980s. Murders and corruption associated with that lucrative but illegal enterprise are revealed in Fikes’ meticulous review of the 1998 murder of Phil True, the American journalist killed by two Huichols whose illegal cash crop was burned just one year before they murdered True as he hiked alone through their territory. Carlos Castaneda’s influence in stimulating True and many other Americans longing to locate, or perhaps to become shamans, to visit the Huichol is carefully documented by Fikes, who is Castaneda’s most severe anthropological critic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

During my first year at the University of California, San Diego I gained insights about hierarchical European societies by taking Professor Herbert Marcuse’s “Theories of Society” class. In Fall of 1970, I began what became my lifelong study of shamanism with Dr. Robert Levy, a psychiatrist and psychological anthropologist. Reading numerous publications about shamanism assigned by Dr. Levy taught me that shamans were leaders in simpler societies that valued group cohesion and adaptation to nature.

By 1976 I had learned enough about indigenous Mexican tribes, after taking several graduate classes in social anthropology at the University of Michigan, to select the Huichol as the people to host my doctoral fieldwork. My first visit to the Huichol ceremonial center at Santa Catarina in July of 1976 was remarkable. I was given two peyotes to aid me in completing a solo, all-night vigil at the shrine of Grandfather-Fire. My first Huichol shaman-mentor, Bonales, must have been impressed by my description of unusual experiences I had at that shrine, one of many I was taken to visit. Bonales invited me to return and stay with him and his family. Another Huichol guided me to see a young Kieri plant, enabling me to become the first anthropologist to photograph a Kieri. One week of experiences in Santa Catarina convinced me I had found the ideal place to research Huichol rituals and shamans.

Twenty years later, after staying with two Huichol families during 23 visits to Santa Catarina, I arrived in the Huichol settlement of Tuxpan de Bolaños, to deliver from the Smithsonian Institution to Tuxpan elders anthropologist Robert Zingg’s 1934 silent film footage. Following a public screening of Zingg’s film footage, Jesús González, the protégé of Kieri whose biography I am publishing, approached me to let me know he was 13 years old in 1934, when Zingg filmed rituals depicting his Huichol relatives and friends, whose images González recognized in the film.

What I learned from Jesús González and three Huichol shamans from Santa Catarina profoundly changed me. According to Huston Smith, my 2011 book, Unknown Huichol, “will become a landmark in comparative religion.” Professor Emeritus Conrad Kottak praises Beyond Peyote as “well-written and innovative …an original contribution to studies of Huichol ethnohistory, shamanism, and comparative religion.” My hope is that readers of Beyond Peyote will appreciate its empathetic and comprehensive portrait of Huichol shamanism as well as its scholarly rigor.